Be At Leisure, And Know That I Am God

In the economic world of today, “9 to 5” is being replaced with “24/7.” More and more people feel as if they are always “on the clock.” In fact, because of smartphones, they are discovering they can’t leave work when they go home. There’s no downtime, no freedom from an electronic distraction, no chance to just be.

This is one aspect of living in the age of machines. It also changes our mindset. The standards of function and profit are no longer applied to work alone. “What does this do for me? What do I get out of it?” are questions people ask of everything. They’re asked even of other people.

“One does not work to live, one lives to work,” goes the famous quote by Max Weber, the German philosopher of capitalism. That’s the rule of modern life, a rule that is very limiting.

There is an escape from the confinement of work: it is the idea of leisure, a word that is often misunderstood. Being at leisure is not the same as “killing time” or engaging in a hobby. Rather, true leisure shares an affinity with contemplative prayer. It requires us to step away from the daily pressures and obligations of work and all that is utilitarian. We need to slow down and open ourselves in a receptive way to reality, to creation, to that which God said, “It is good.”

To be at leisure means to join God in this affirmation. Leisure refreshes bodies that are tired and relieves senses that are over-stimulated. In its deepest sense, leisure is sacred time. We “waste” time with God instead of using it for a more “practical” purpose. Perhaps leisure can be described as that which exists for its own sake, that “something else” which makes life worth living and preserves our humanity. True leisure is akin to art.

The frantic pace of modern life threatens the existence of leisure. Many confuse it with the relentless pursuit of entertainment, others feel guilty when they make time for it. But leisure is more than an escape from work: it is a sanctuary for preserving the values of being human.

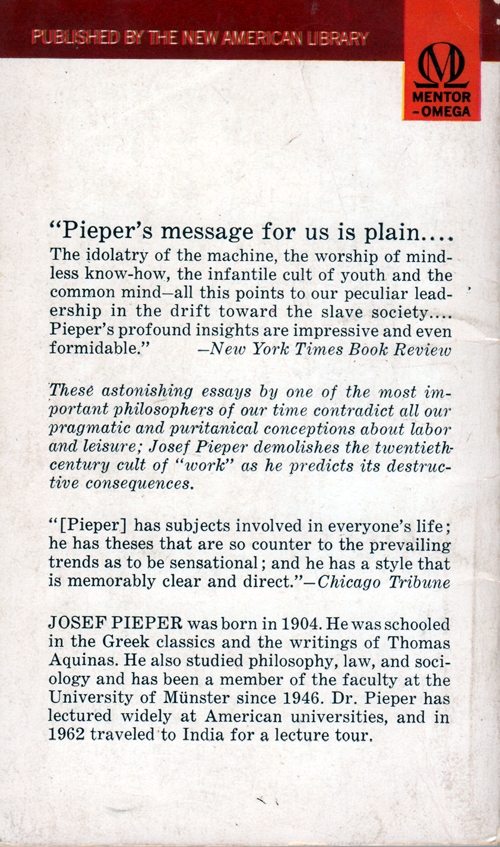

What follows is an excerpt from an excellent little book, Leisure: The Basis of Culture. It was written by Josef Pieper, a twentieth-century philosopher in the tradition of St. Thomas Aquinas.

Pieper describes leisure as a mental and spiritual attitude, characterized by non-activity and inward calm. Leisure means to not be busy, but to let things happen. It is a form of silence which is a prerequisite for the apprehension of reality. Only the silent hear. In a world of total labor, this contemplative attitude gets crowded out. With it goes the foundation for an inspired and life-giving culture.

His book is worth reading to digest the fullness of his message. Pieper can inspire us to heed the divine call that nourishes our lives: “Be at leisure, and know that I am God” (Psalm 46:11).

The following excerpts are from the 1952 edition published by Pantheon Books, New York:

“Leisure, it must be clearly understood, is a mental and spiritual attitude – it is not simply the result of external factors, it is not the inevitable result of spare time, a holiday, a week-end or a vacation. It is, in the first place, an attitude of mind, a condition of the soul, and as such utterly contrary to the ideal of ‘worker’ in each and every one of the three aspects under which it was analyzed: work as activity, as toil, as a social function.

“Compared with the exclusive ideal of work as activity, leisure implies in the first place an attitude of non-activity, of inward calm, of silence; it means not being ‘busy,’ but letting things happen.

“Leisure is a form of silence, of that silence which is the prerequisite of the apprehension of reality: only the silent hear and those who do not remain silent do not hear. Silence, as it is used in this context, does not mean ‘dumbness’ or ‘noiselessness:’ it means more nearly that the soul’s power to ‘answer’ to the reality of the world is left undisturbed. For leisure is a receptive attitude of the mind, a contemplative attitude, and it is not only the occasion but also the capacity for steeping oneself in the whole of creation.

“Furthermore, there is also a serenity in leisure. That serenity springs precisely from our inability to understand, from our recognition of the mysterious nature of the universe; it springs from the courage of deep confidence, so that we are content to let things take their course; and there is something about it which Konrad Weiss, the poet, called ‘confidence in the fragmentariness of life and history’. . . .

“Leisure is not the attitude of mind of those who actively intervene, but of those who are open to everything; not of those who grab and grab hold, but of those who let the reins loose and who are free and easy themselves – almost like a man falling asleep, for one can only fall asleep by ‘letting oneself go.’

“Sleeplessness and the incapacity for leisure are related to one another in a special sense, and a man at leisure is not unlike a man asleep. When we really let our minds rest contemplatively on a rose in bud, on a child at play, on a divine mystery, we are rested and quickened as though by a dreamless sleep. Or as the Book of Job says, ‘God giveth songs in the night’ (Job 35:10). Moreover, it has always been a pious belief that God sends His good gifts and His blessings in sleep. And in the same way His great, imperishable intuitions visit a man in his moments of leisure.

“It is in these silent and receptive moments that the soul of man is sometimes visited by an awareness of what holds the world together, only for a moment perhaps. . . .

“Leisure appears in its character as an attitude of contemplative ‘celebration,’ a word that, properly understood, goes to the very heart of what we mean by leisure. Leisure is possible only on the premise that man consents to his own true nature and abides in concord with the meaning of the universe (whereas idleness, we have said, is the refusal of such consent). Leisure draws its vitality from affirmation. It is not the same as non-activity, nor is it identical with tranquility; it is not even the same as inward tranquility. Rather, it is like the tranquil silence of lovers, which draws it strength from concord. . . .

“And we may read in the first chapter of Genesis that God ‘ended His work which He had made’ and ‘behold, it was very good.’ In leisure, man too celebrates the end of his work by allowing his inner eye to dwell for a while upon the reality of the Creation. He looks and affirms: it is good.

“Now, the highest form of affirmation is the festival. . . . To hold a celebration means to affirm the basic meaningfulness of the universe and a sense of oneness with it, of inclusion within it. In celebrating, in holding festivals upon occasion, man experiences the world in an aspect other than the everyday one.

“The festival is the origin of leisure, and the inward and ever-present meaning of leisure. And because leisure is thus by its nature a celebration, it is more than effortless; it is the direct opposite of effort.

“Because Wholeness is what man strives for, the power to achieve leisure is one of the fundamental powers of the human soul. Like the gift for contemplative absorption in the things that are, and like the capacity of the spirit to soar in festive celebration, the power to know leisure is the power to overstep the boundaries of the workaday world and reach out to superhuman, life-giving existential forces that refresh and renew us before we turn back to our daily work.

“Only in genuine leisure does a ‘gate to freedom’ open. Through that gate man may escape from the ‘restricted area’ of that ‘latent anxiety’ which a keen observer has perceived to be the mark of the world of work, where ‘work and unemployment are the two inescapable poles of existence.’”

Pieper, Josef. Leisure: The Basis of Culture. New York: Pantheon Books, 1952.